|

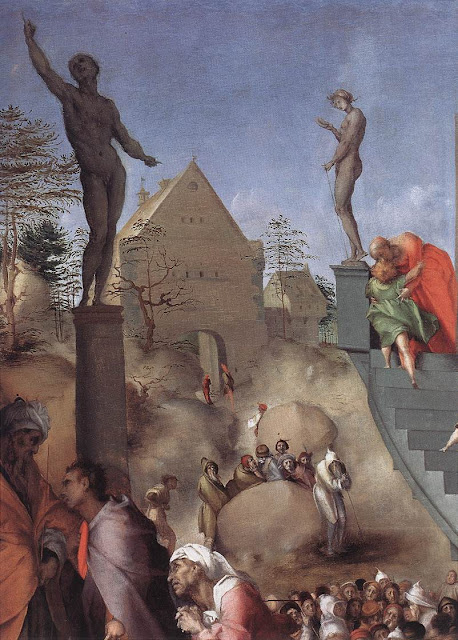

Fra Fillippo Lippi, Confirmation of the Carmelite Rule, c. 1432, Fresco, Museo di Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence. |

A painter who developed alongside Uccello in Florence was Fra Fillippo Lippi. As his name suggests, he was a monk, a young Carmelite friar. An unwanted child, Lippi was raised in the Carmelite friary of the Carmine, where he took his vows in 1421. Unlike the Dominican Fra Angelico, Lippi was not cut out for the religious life, and infamously scandalized his brethren by running off with a nun, Lucrezia Buti, who had been persuaded to pose as a model. She bore his son Filippino and a daughter Alessandra. Despite the couple being released from their vows and marrying, Lippi insisted on signing himself "Frater Philippus". Never one to miss an opportunity to embellish a biography, Vasari really pulled out all the stops, throwing in capture by Barbary pirates and portrayed a headstrong, wordly artist at odds with the strictures of the renaissance church. Where art was concerned Lippi took the best model available, Masaccio, whose frescoes where available to see in the Carmine. According to Vasari, Lippi’s first painting was done in 1432, in the Carmine, a fresco showing the Confirmation of the Carmelite rule. Vasari was proved right when Lippi’s fresco was discovered in 1860 beneath a layer of plaster in the convent. It took Lippi some time to get into his stride as a painter; his early Madonna of Humility is a curious blend of Masaccio and bizarre experimentation. Of interest here is Lippi’s treatment of angels, who as Antal notes do not conform to the antique model, but have the faces of Florentine urchins, and pretty ugly ones at that.[1]However, Fra Fillippo introduced a new standard of beauty to Florentine art with his later Madonnas, his portraits, such as the first double portrait with a landscape (New York) and his fresco cycle at Prato, especially Herod’s Banquet. Botticelli became Fra Fillippo’s pupil and the swirling rhythms and effortless grace of this picture would re-appear in the younger artist’s work.

|

Fra Filippo Lippi Herod's Banquet, 1452-65, Fresco, Duomo, Prato. |